JOSIP JELAČIĆ – BAN OF CROATIA

Ante Čuvalo – Chicago

(Published in: Review of Croatian History, IV. no. 1, 2008, pp. 13-27)

This year (2008) marks the 160th anniversary of the 1848 revolution in which Ban Jelačić played a significant role. The short survey of Jelačić’s life that follows is written mainly for young Croatians around the world so that they may have a better understanding of Jelačić, the times in which he lived, and Croatian history in general.

Introduction

In 1848, a revolutionary wave swept across Europe, except in England and Russia. In England, the revolutionary pressures were deflated by reforms; in Russia, no action could be undertaken because of the cruelty of the tsarist regime.

A mix of severe economic crisis, romanticism, socialism, nationalism, liberalism, raw capitalism, growing power of the middle class, the misery of the workers and peasants (that still included the serfdom), the slipping power of the nobility and, in some countries, royal authoritarianism bordering with absolutism, created a volatile blend that brought about the Year of Revolution! The prelude to the 1848 events began among the Poles in Galicia in 1846, a civil war in Switzerland in 1847, and an uprising in Naples in January of 1848. However, in February 1848 the French ignited a fire that spread rapidly across the continent.

In the Austrian Empire liberals demanded a written constitution, which meant a quest for greater civil liberties by curbing the power of the Habsburg regime. When such attempts failed, popular revolts ensued, especially among the students and urban workers. At the beginning there was an alliance of students, middle-class liberals, workers, and even peasants. Under such pressure, the monarchy gave in to the demands and ultimately collapsed. But because of disunity among the revolutionaries, the traditional forces and the military establishment regained courage and strength, and in the end crushed the revolution.

The Hungarians were at the forefront of the revolution in the Habsburg Empire and in March 1848 promulgated a liberal constitution in their part of the monarchy. However, what Hungarians demanded for themselves they were not willing to give to non-Hungarians. Namely, they stood firmly for a unitary Hungary in which Croatians and other non-Hungarians would not have political and cultural rights. It should be remembered that Croatia was a separate kingdom united with Hungary under the crown of St. Stephen, and not a Hungarian province. But Hungarian imperialists, including Lajos Kossuth, the key man of the revolution, were liberals only for themselves. Because of their narrow-mindedness the Hungarians pushed the revolution over the edge and turned it into a disaster for themselves and others.

***

Revolutions bring out an array of forces and passions and produce both heroes and villains. Depending on the perceptions, interests, and judgments of the observer. One example of such a revolutionary is Josip Jelačić, Ban of Croatia. To the Croatians, and to other Slavs in the empire, he was a hero, as he was to the supporters of the Habsburg monarchy. To the Hungarians and other anti-Habsburg forces, Jelačić was a villain. He fought the Hungarians to get more independence for his native Croatia. He also championed national and individual rights of Slavs to be equal with those of Hungarians and Germans within the empire. Thus, his goals were progressive and noble. But by fighting the Hungarians and revolutionaries in Vienna he supported the Habsburgs, whom he saw as the lesser of two evils. Because the Hungarian revolutionaries were portrayed as liberals and had the sympathy of the West, Jelačić was depicted as a reactionary. But the same pro-Hungarian forces outside the empire did not want to see the sinister side of Lajos Kossuth and his bogus liberalism.

Josip Jelačić Before 1848

Ban Jelačić came from a family deeply rooted in the Habsburg military tradition. For two hundred years it had given officers to the empire, especially to the Military Frontier region in Croatia. He was the oldest son of Baron Franjo Jelačić Bužimski, a Field-Marshal,1 who distinguished himself in the war against Napoleon.2 His mother was Anna Portner von Höflein.

Josip was born on October 16, 1801 in the fortress of Petrovaradin, which was one of the well-known forts in the long struggle against the Turks. Military spirit and smell of gunpowder were a part of Josip’s life from the time of his birth; it was no wonder then that he kept the family tradition and became an officer.

As an eight-year-old boy Josip had the honor of being presented to Emperor Francis I, who recommended he be accepted at the Theresianum in Vienna. Shortly after his father’s death in 1810, Josip entered the famous Theresianum, where new military and administrative personnel of the empire were trained.

Jelačić was an excellent student with a variety of talents. Because of his eloquence his teachers advised him to become a lawyer, but he preferred being a soldier.3 Besides Croatian, he spoke German, Italian, French, and Magyar.4 In 1819, he graduated from the academy with honors, and as a Sub-Lieutenant he was sent to Galicia. Jelačić was loved by his peers, respected by his soldiers, and recognized as an excellent officer by his superiors. He loved army life and it seems that he fascinated everyone around him. His vigor, exuberance, good temper, wit, bravery, and even his talent for poetry brought him fame, good fellowship and popularity in the military circles.5

Jelačić’s joyous and carefree military spirit was interrupted, however, by a sudden and serious illness in 1824. For a year he recuperated at his mother’s house in Turopolje, near Zagreb. During that year he wrote a book of poems, which was published in 1825 and reissued in 1851. Suffering added to the depth of his character without affecting his vigor and love of life.

In 1825, Jelačić returned to his friends and comrades in arms, who were at this time in Vienna. He was again “the beginning, middle, and end of all proceedings” among his peers.6 After a short stay in Vienna, he was sent again to Galicia. In 1830, he became a Lieutenant Captain in the Ogulin regiment at the Croatian Military Frontier, where he was stationed. One year later he and his regiment were in Italy, where he served under the renowned General John Joseph W. Radetzky. About Jelačić the General once stated: “I expect the best of him; never yet have I had a more excellent officer.”7 After his return from Italy in 1835, Jelačić stayed permanently in Croatia. In 1837, he became a Major and was assigned as adjutant to the military Governor of Dalmatia, where he gained much valuable administrative experience and also had a chance to learn more about his native land and its people. Four years later he became a Colonel and returned to the Frontier troops.

At the Frontier territory, Jelačić had military and administrative responsibilities. In both areas he became not only very efficient but also popular. With his soldiers he was fair, and he cared for their well being. He even abolished corporal punishment. As an administrator, he would hear complaints of the local people and proved to be a fair arbitrator. He was well-known in the villages, attending various community gatherings and celebrations, including dancing the kolo (circle dance) at weddings.8 Such demeanor contributed to his fame among the soldiers and civilians.

A German officer in the Habsburg armed forces, who served under Jelačić in 1848, gives the following personal and vivid account of Jelačić:

The impression which this distinguished officer made upon me at the very first moment was most prepossessing; and it has since become stronger and stronger, the more I have had occasion to observe him in all the situations of life—in battle, and in cheerful society. He is an extraordinary man; and Austria may deem herself fortunate in possessing him and Radetzky precisely at the same moment.

Jellachich is of the middling height and size. His bearing is upright and truly military; his gait quick, as indeed are all his motions. His face, of a somewhat brownish tinge, has in it something free, winning, and yet determined. The high forehead, under the smooth black hair, is very striking. The eyes are large, hazel, and full of expression. In general, there is something extremely calm and gentle in their glance; but, when the Ban is excited, they flash, and have so stern—nay, so wild—a look as to curb even the most daring fellows. At the same time he is the mildest and kindest of officers. When but captain, he had almost entirely abolished blows in his company; and, while commanding the second Banat regiment as Colonel, there were not so many punishments in it in a year as there were formerly in a month.

Here is just one instance of the care which the Ban takes of his men. Last winter, when he was still Colonel, Lieutenant Field-marshal D——, Who commanded on the frontier, fixed a certain hour for inspecting the regiment. There was a piercing frost, and the soldiers shook with cold; but the Lieutenant Filed-marshal sat enjoying himself over his bottle at the tavern, leaving the regiment exposed to the cutting wind on the parade, to be frozen or petrified, for what he cared.

Jellachich waited nearly an hour beyond the appointment time; and the General not yet making his appearance, he ordered the regiment to disperse quietly. No sooner had it obeyed, than the General appeared upon the ground; but it was then too late, and the inspection could not take place.

This affair is said to have produced a great sensation, and, when reported to Vienna, to have been entered in the black book. But March has expunged this, like many other matters; and the Ban was in a few weeks promoted from Colonel to Lieutenant Field-marshal. The whole army, some antiquated nobs perhaps excepted, rejoiced at it. But this was nothing to the rejoicing with which, on the appointment of Jellachich to the office of Ban, he was received in Croatian and Slavonia, and which is said to have defied description.

Never was general more beloved by his troops. Wherever he shows himself in a military village, all—old and young, little boys and aged men, ay, and pretty girls, too—all rush out to see him, to shake hands with him, and to greet him with one Zivio! [Long live!] after another. In battle, after the most fatiguing march; in bivouac, exposed to pouring rain; wherever and whenever the border-soldier espies his Ban, he joyously shouts his Zivio! and for the moment, bullets, hunger, weariness, and bad weather, are nothing at all to him.

The scene that I witnessed when the Ottochans, who had been with me in Peschiera, and who arrived a few days after me in Croatia, were reviewed by the Ban, I shall never forget. Old border-soldiers—who had often braved death, and not flinched when the bombs at Peschiera fell in their ranks—wept for joy, when Jellachich praised them for their good behaviour. And yet he told them at once that the repose at their own homes which they had so richly earned and hoped to enjoy could not yet be granted to them; that, after a few days’ rest, they must start for Hungary, to engage in fresh conflicts.

… His voice is soft and pleasing, but perfectly distinct when giving the word of command. He is unmarried; has not much property; lives simply and frugally, applying almost all that he can spare to the support of his soldiers.9

The above biographical account, even if from a friendly officer, is impressive for any individual and it supports other first-hand accounts about Jelačić.

The Political Situation in Croatia in the 1840s

The political and cultural life in Croatia was very vibrant during the 1840s. Young intellectuals were full of enthusiasm for national revival. National newspapers began to appear, book publishing flourished, and even the first Croatian national opera premiered in Zagreb in 1846. Political life was dynamic and exciting, especially after use of the “Illyrian” name was forbidden in 1843. The language question became one of the major issues. The Magyars decreed their language to be the only official language in the kingdom; the Croatians, however, rejected this resolution of the Hungarian Diet (Parliament). The question of language was in the forefront of the policies of Magyarization by which Lajos Kossuth and other nationalists demanded an integrated Hungary stretching from the Carpathian Mountains to the Adriatic Sea. Hungarian pseudo liberalism denied others what Hungarians were demanding for themselves. On the other hand, nationalism in Croatia, and other non-Magyar regions was not less intense then that of the Magyars. It was inevitable that these forces and passions would clash sooner or later.

The Military Frontier and the army did not play a significant role in the national movement. But it had not been isolated from the spirit of the time either. There were demands from the Frontier for better living conditions, for reduction of military obligations, and even for the abolition of the region as a separate political unit from the rest of Croatia.10

Jelačić himself was under the influence of the leaders of the “Illyrian” movement, like Ljudevit Gaj and others. However, this did not prevent him from being a loyal officer of the empire.

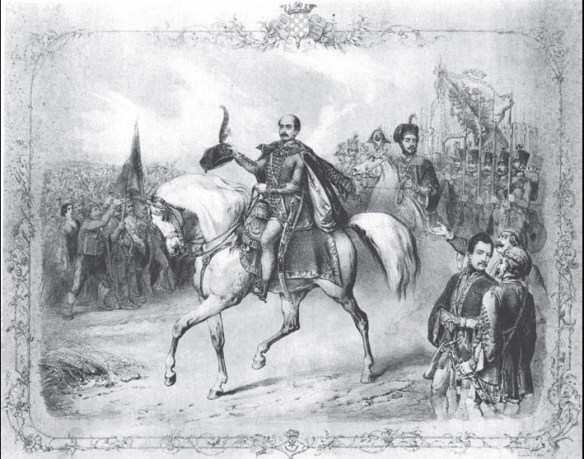

Jelačić and the Events of 1848

Scene from Jelačić’s ceremonial installation on the position of Croatian ban in Zagreb, June 4, 1848 (Contemporary engraving published in Zagreb’s weekly Svijet on May 19, 1928)

With Ferdinand’s approval of Magyar self-rule in March 1848, a new situation developed in the relationship between Hungary and Croatia. From that moment, Hungarians were responsible to their Diet (Parliament) and not to the emperor/king. (The official title of the Austrian emperor in Hungary and Croatia was king, not emperor.) The king would no longer be able to veto resolutions and laws passed by the Diet in Hungary even if such laws were directed against other nations and nationalities in the kingdom. Therefore, non-Magyars were thrown at the mercy of the ruling nation. The results of this development were soon felt. The Hungarian Diet passed legislation by which Croatian political and cultural distinctions were to be obliterated. In one of his speeches Kossuth declared that there had never been a Croatian name or a Croatian nation.11

A provisional national assembly was called in Zagreb on March 25, 1848 in order to respond to the dramatic changes in Hungary and their effects on Croatia. This was done on the initiative of some leading Croatian liberals. However, only a few days earlier one of the conservative nationalists, Franjo Kulmer, who had good relations with the Court, went to the capital to advocate the Croatian cause among influential circles in Vienna. Interestingly enough, Croatian nationalists of both liberal and conservative political persuasions, wanted Jelačić to lead the nation through this growing crisis. They believed that a man with his popularity and character, who had also the army behind him, could make a stand against the Magyars and their imperialistic appetite. He was a nationalist but a Habsburg loyalist who believed that the only way to stop the Hungarians was to be on the side of Vienna. On March 23, 1848, Kulmer succeeded in Vienna to get Jelačić nominated as the new Croatian Ban (Viceroy); two days later the provisional assembly in Zagreb unanimously acclaimed him for that position without knowing about the Vienna nomination.

However, no one asked Jelačić if he would accept the nomination. On the contrary, he was not eager to get involved in the political arena. On March 26, 1848 he wrote to his brother: “Indeed we live in extraordinary days. That I am Ban, Privy Councilor, and General you will know already…. I can forbid no one to nominate me; but if they ask me whether I wish to be Ban, then decidedly I say No!”12 He was at the same time promoted to the rank of Lieutenant Field-Marshal and Commanding General in Croatia, including the Military Frontier.

Jelačić, therefore, became Ban without the approval of the government in Hungary, so in the Magyar eyes it was an illegal appointment. This defiance made the new Ban completely independent from Pest. Hungarians began giving orders to the Frontier regiments and to local governments in Croatia, but Jelačić issued a proclamation forbidding anyone to take orders from anyone except himself. He officially broke all relations with Hungary, leaving it to the new Croatian Sabor (Parliament) to renegotiate Hungarian-Croatian relations.

The Hungarian government tried to stop the meeting of the Sabor. Due to Magyar pressure, the Habsburg emperor ordered Jelačić to call off the meeting. But Jelačić declared that “he could not obey the order of his sovereign who does not have his free will.”13 The Sabor was solemnly opened on June 5, 1848. It confirmed all the decisions made by Jelačić since he took office, among them abolition of serfdom and the law of equal taxation. This finally ended feudalism in Croatia. The Sabor then proposed a structural change of the Habsburg empire. It advocated federalism, in accordance with the wishes of other Slavs in the realm. This Sabor deliberated in full freedom and independence from Vienna and Pest. It proved itself to be a capable political body of free representatives.14

Jelačić’s political views, one could say, were shaped by the spirit of the time and by his military and family background. He desired to make a big step forward for his Croatian and other peoples in the empire by advancing federalism, but he was against any radical revolutionary undertakings in this process. His national feelings can be seen already in his first proclamation as Ban of Croatia, which states:

The good of the people and country; that is my wish and my sole aim. I desire that our country may be strong and free…. In all my thoughts and deeds I will be the true expression of the nation’s will and thoughts. Therefore I intend to walk and continue in the path, which shall lead our country to happiness and glory.

The revolution has shattered and overthrown the old foundations of social life and the national and governmental relations, especially those with our old ally, Hungary—therefore, remembering our ancient league with the crown of Hungary, it is necessary to renew the connection in spirit of freedom, self respect, and equality, and to form a basis worth of a free and heroic nation, though on our side all relations with the present Hungarian Ministry must be broken off….15

In his speech on the day of the opening of the new Sabor Jelačić reiterated his position:

Brothers, all the relationships between governments and the people, between state and state, between nation and nation have to be based on freedom, equality and fraternity. That demands the powerful spirit of the time in which mankind is progressing toward its perfection. On this basis we too will base our relationship with the Magyars…. In an unfortunate case, if the Magyars show themselves to be not like our brothers toward us our kinsmen in Hungary and assume the role of oppressor, let them know that we said it, the time has passed when one nation ruled over another. We are ready to prove this to them even with a sword in our hand, keeping in mind the words of our honorable Ban Ivan Erdedi: ‘Regnum Regno non praescribit leges.’ [Kingdom does not prescribe the laws to another kingdom.]16

Jelačić stressed national rights very strongly, but on the other hand he believed that the Habsburgs would respect the liberal “spirit of the time” and help to achieve the equality of various nations in the empire. He had perhaps too much faith in the Habsburgs’ good will and willingness to change. In May of 1848, Jelačić wrote to the Archduke Karl; “Is it possible that all will get their freedom and only we Croatians and Slavonians will be left to the despotism of the Magyar Ministry?… We ask you to respect us now or never!”17 He was looking for help from Vienna. It seems, however, that he already suspected help would not be forthcoming.

On June 12, 1848, Jelačić and his Council arrived in Innsbruck to present the emperor the Sabor’s recommendations; but two days earlier Hungarians had persuaded Ferdinand to dismiss the Ban. However, Jelačić did not know this when he met with the emperor. Magyar representatives were present at that audience. Furthermore, Archduke John was appointed to mediate between the Magyars and the Croatians.

Jelačić’s visit to Innsbruck was a turning point in his policies toward Vienna. Kulmer and his friends at the Court gave the impression that Vienna was fully behind the Croatian cause. One of Jelačić’s companions in Innsbruck, F. Žigović, wrote to Zagreb: “…from the highest to the lowest [person] here is disposed with the friendliest spirit toward us.”18 Jelačić agreed to call upon the Croatian soldiers in Italy to continue the fight for the empire there. He began to think as a Habsburg general again. But the contradictory situation of Croatia and her Ban became more and more evident.

To look for the reason of Jelačić’s support of the dynasty in Archduchess Sophie’s weeping on his shoulders, as some do,19 is naïve, or that the only freedom he knew was “that which he proclaimed with his sword”20 is perhaps a willful misjudgment of his character. He definitely had a high vision for Croatia and the freedom of its people, as can be seen from his speeches. He must have had honorable political goals — perhaps even assurances — in mind when he decided to support the dynasty. Even Camillo Cavour of Piedmont recognized that Jelačić’s demands were in accordance with the demands of other Slavs and not based on Habsburg reactions.21

Jelačić learned about his dismissal as Ban while returning from Innsbruck, but he ignored it and continued to function as though nothing had changed. The Court in Vienna did press the case. Hungary, however, took the emperor’s order seriously by trying to get some anti-Jelačić support in Slavonia. But this did not bring the desired results. In Slavonia Jelačić was received as a national hero. The imperial commissioner, who was to replace Jelačić’s authority as military commander, at Magyar urging, attacked the town of Srijemski Karlovci and a general fight broke out with the local Serbian population. The Sabor in Zagreb passed a resolution to send immediate help to the Serbs, but Jelačić did not rush to engage the fight.

There was another attempt to solve the Hungarian-Croatian crisis by peaceful means. Archduke John called a meeting of Jelačić and Hungarian Prime Minster Battyanyi in Vienna in July of 1848. It is said that Jelačić asked for the impossible because he did not want peace with the Hungarians.22 However, his demands were misinterpreted “in respect of their spirit and intention.”23 The meeting with Battyanyi did not bring any results because the Magyars demanded a total submission on the part of Croatians. It actually ended with a threat of war. Battyanyi declared to Jelačić: “Then we meet on the Drava [river].” “Say rather on the Danube,” responded Jelačić.24 On this occasion in Vienna, Jelačić told the “immense multitude” that came to greet him “I wish a great, a strong, a powerful, a free, an undivided Austria.”25 In response to the Magyar threat he sought to save the Monarchy and Croatia with it.

Soon after, the Habsburg war machine started to move, and Jelačić with it. On September 4, 1848, the emperor restored Jelačić to his rightful position as Ban. Three days later he was on his way from Zagreb toward the Drava, or rather toward the Danube. In his manifesto to the people before he moved into Hungary he declared: “We want a strong and free Austria…we want equality, and the same rights for all nations and nationalities living under the Hungarian crown. This was promised by the words of our sovereign to all nations in the Monarchy in March [1848].”26 Obviously he had taken Ferdinand’s promises seriously.

On September 11, Jelačić crossed the river Drava. His army, however, was not a unified fighting force. The volunteers were undisciplined and not of much help. He sent 12,000 volunteers home after the battle of Pákozd on September 29.27 The battle had been fought to a draw, and neither Jelačić nor the Hungarians were eager to renew the fight. Jelačić waited for 7,000 more Graničars (men from the Military Frontier), but they never arrived. Meanwhile revolution broke out in Vienna and Jelačić turned his forces toward the capital.

There are indications that Vienna had not wished Jelačić to enter Pest after he crossed the Drava. For example, the material support given him by the Court had not been significant. Also, the seven thousand Graničars under General Roth did not follow Jelačić’s plan. Meanwhile, Count Lamberg was in Pest seeing if things could be worked out between Hungarians and the Court. It seems that Jelačić was being used to put pressure on the Magyars, while Croatian interests were simply ignored.28 One interpretation of these events is that Hungarian conservative forces had planned this “little war” in order to stop their Hungarian liberal colleagues in their radical pursuits.29

Ban Jelačić leading his troops during the battle of Schwechat near Vienna, October 30, 1848 (Contemporary engraving published in Zagreb’s weekly Svijet on May 19, 1928)

Jelačić’s march to Vienna signified a major change of purpose in his struggle. He began fighting the Hungarian oppression and now he found himself fighting Austrian revolutionaries and also a war of the Habsburgs against the Magyars. He was appointed the Royal Commissioner of the Hungarian kingdom, but this did not mean much in reality. As soon as General Windisch-Gratz and his troops joined him near Vienna, his role became secondary. From then on, Windisch-Gratz commanded the army and events. Jelačić did win a few victories for the Habsburgs in Hungary, but these were the exploits of a Habsburg General, not of a Croatian Ban. In August 1849, Jelačić fought for Petrovaradin, his native town. It surrendered to him on September 6, 1849, ending his last military campaign and his military career as well.

Tragic Ending

Soon after the revolutionaries were pacified, Jelačić learned about the “rewards” for his loyal service. Oppression, centralization, and Germanization were equally applied to the loyalists and to the revolutionaries. This was a bitter disappointment to Jelačić. His popularity at home declined. The former pro-Magyar forces in Croatia came to power again. He was Ban in name only. From 1849 to 1851, he attended all the meetings of the government in Vienna. He resisted oppressive measures but seeing that he could do nothing about them, he stopped going to Vienna. At his last meeting he told the emperor: “Highness, there is not a single man satisfied in the country.”30 But things did not improve. Jelačić himself was under police surveillance. Even his wife’s chamber maid was in the police service.31

A contemporary English diplomat, Sir Robert Morier, who visited Croatia soon after the revolution and even took private crash-courses in Croatian, states the following about the Habsburg treatment of Jelačić, whom he describes as “a most remarkable man:”

If ever, since the foundation of the Order of Maria Theresa, an Austrian subject deserved the Grand Cross of the Order by the fulfillment on the largest scale of the conditions originally stipulated by the rules of the Order, it was the Ban. Those rules, as is well known, recognize by preference the claims of those who have successfully achieved some great exploit either without or in contradiction to orders received from their superiors. Now, this latter was achieved by the Ban upon a scale rarely seen in history. As an outlaw he places himself at the head of an entire nation, declares war on his own responsibility, marches successfully into the very heart of the enemy’s country, and then by a brilliant maneuver, after a doubtful battle, comes to the rescue of the capital of the Empire. Nevertheless, the Chapter of the Order (on the very same day, if I am not mistaken) awarded to Prince Windishgrätz, for his successful putting down of the émeute at Prague, the Grand Cross of the Order; and to the Ban, for the services by him rendered, the Commander’s Cross only. Again, Prince Windishgrätz was named Field-Marshal, the Ban General; but two years later it was retrospectively stipulated that he should not advance towards the grade of Field-Marshal, otherwise than if he had become General by seniority.32

The main reason for such treatment of the Ban and the Croats, according to Morier, was “the contempt which the Austrian German” has for the Austrian Slav “combined with the very real fear with which the numerical superiority of the latter inspires him.” Furthermore, the Englishman describes the Habsburg ungratefulness as follows: “…I must confess that, with every wish to make allowance for the difficulties of the situation, it yet seems to me that a more wholesale act of injustice, ingratitude, and bad faith, a display on a large scale of mean and paltry spirit, grosser fraud, more clumsily veiled, it would be difficult to meet with in all the pages of history.”33

Jelačić was politically active until 1853. His policy was to save what could be saved. By his efforts the Zagreb diocese became an archdiocese, independent from the Hungarian church hierarchy. He organized the National Theatre in Zagreb, in which only Croatian was used. He succeeded in getting Juraj Strossmayer nominated as bishop of Djakovo. And a number of other cultural advances are also attributed to him.

In 1850, Jelačić married Countess Sophie von Stockau. He was forty nine and she was sixteen years old. On the occasion of the marriage in 1854, he received the title of Count from Francis Joseph, the emperor. But already at that time his health was waning. A year later his only child died. His public life was ended and he was tormented by all that had happened since the euphoric days at the beginning of 1848. He told one of his closer friends: “The Austrian government is killing me. I do not have any organic sickness. I am healthy. I have full strength of the body, but I am dying. Austria, in which I have believed, is destroying me.”34

Jelačić died on May 20, 1859, a man whose ideals were destroyed by a regime which he helped to save. He was buried in his Novi Dvori, near Zagreb, by the side of his only child.

Conclusions

Ban Jelačić’s equestrian monument in Zagreb on original position at Ban Jelačić’s Square (on the postcard from late 1920s). The monument was erected in 1866. Removed by communist authorities in 1947, it was returned to the square after the collapse of communist regime in 1990.

Jelačić was a product of both national and pro-Habsburg feelings and loyalties which he did not perceive to be contradictory. When he entered Zagreb on his inaugural day, the whole city came out to greet him. It was an historic occasion. Croatians and many other Slavs looked at him as the only hope for a better future in the Monarchy. He declared that his only goal was the good of the people and his native land.

On the other hand, when he came to Vienna to meet Battyanyi, he was greeted again as a hero, but now by the Vienna crowd. He declared to them “I wish a great, strong, powerful, free, and undivided Austria.” He tried to synthesize these two conflicting goals. He believed that the first could be achieved through the second one. But the Habsburgs had other aims and plans for him, Croatia, and the empire.

Jelačić has been attacked from many sides, as a Panslavist, as a pro Russian, as an Austrophile, and a reactionary, among other and often contradictory labels. Even after his death, he was a hero to some and a villain to others. To Croatians he became a symbol of the struggle against the Magyars and a martyr of the devious Austrian regime. A monument was erected in the main square in Zagreb to his honor and patriotic songs about him carried his name to the younger generations. After the Second Word War, however, he was condemned once more as an antirevolutionary and reactionary figure. His monument was removed from public eye and the songs were banned. But his name could not be obliterated from the memory of the Croatian people. As soon as the communist regime in Croatia collapsed his monument was returned to its rightful place and Zagreb’s main city square bears Jelačić’s name again. He continues to be a symbol of Croatian enthusiasm for freedom and independence.

Der kroatis che Banus Josip Jelačić

Zusammenfassung

Der Autor verfasste diesen Überblick über Jelačić“ Leben anlässlich des 160-jährigen Jubiläums der 1848-er Revolution und seines Antritts in den Amt des kroatischen Banus in demselben Jahre. Dieser Überblick ist vor allem den jungen Kroaten zugedacht, die außerhalb Kroatiens leben und die grundsätzliche Informationen über das Leben und politische Tätigkeit des Banus Jelačić erfahren wollen. Der Aufsatz ist hauptsächlich aufgrund zugänglicher Literatur geschrieben und bezieht sich größtenteils auf die wichtigste Periode in der politischen Tätigkeit des Banus Jelačić – auf die Revolutionsjahre 1848-1849. Zu dieser Zeit war Jelačić nicht nur die hervorragendste Person der kroatischen Politik, sondern auch ein wichtiger Teilnehmer an den Geschehnissen in der Habsburgermonarchie im Ganzen.

1 Jellachich, Ban of Croatia,” Eclectic Magazine 16 (March 1849), p. 359.

2 E. F. Malcom Smith, Patriots of the Nineteenth Century. New York: Longmans and Green, 1928, p. 55.

3 Ibid., p. 56.

4 “Jellachich,” Eclectic Magazine, p. 359.

5 Ibid., p. 359.

6 Ibid., p. 360

7 Smith, Patriots, p. 58.

8 Ibid., p. 59.

9 W. baron. Scenes of the Civil War in Hungary in 1848 and 1849; with the Personal Adventures of an Austrian Officer. Philadelphia: E.H. Butler & Co., 1850, pp. 19-23.

10 Gunther E. Rothernberg, “Jelačić, the Croatian Military Border, and the Intervention against Hungary in 1848.” Austrian History Yearbook, Vol. 1, 1965, p. 50.

11 Lovre Katić, Pregled povijesti Hrvata. Zagreb: Matica Hrvatska, 1938, p. 218.

12 Smith, Patriots, p. 61.

13 Josip Horvat, Politička povijest Hrvatske. Zagreb; binoza, 1936, p. 182.

14 Vaso Bogdanov, Historija političkih stranaka u Hrvatskoj. Zagreb: NIP, 1958, p. 300.

15 Smith, Patriots, pp. 62-63.

16 Horvat, Politička povijest, p. 184.

17 Enciklopedia Jugoslavije, Vol. IV, S. v. “Jelačić, Josip.”

18 Ibid.

19 Perscilla Robertson, Revolutions of 1848: A Social History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967, p. 281. Sophie was mother of Emperor Franz Joseph I.

20 Ibid., p. 282.

21 Josip Nagy, “Smjernice pokreta g. 1848.” Hrvatsko kolo 14, 1933, p. 27.

22 Robertson, Revolutions of 1848, p. 282.

23 C. Edmund Maurice. The Revolutionary Movements of 1848-9. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1887, p. 383.

24 Smith, Patriots, p. 65.

25 “Jellachich,” Eclectic Magazine, p. 365.

26 Horvat, Politička povijest, p. 193.

27 Ibid., 195.

28 Ibid., 196.

29 Bogdanov, Historija, p. 309.

30 Horvat, Politička povijest, p. 212.

31 Ibid., p. 207.

32 Rosslyn Wemyss. Memoirs and Letters of the Right Hon. Sir Robert Morier, G.C.B. From 1826 to 1876. London: Edward Arnold, 1911, pp. 150-151.

33 Ibid. p. 150.

34 Antonija Kassowitz Cvijic, “Grofica Sofija Jelačic,” Hrvatsko kolo 13, 1932, p. 105.ć